Adventures in Chiropractic: Part 2, the talk

Part 1 can be found here.

The story so far...

A bad case of sciatica had driven my sister to the chiropractor. Knowing little about it other than what I learned during the British Chiropractic Association vs. Simon Singh libel case a decade ago, I decided to do a little investigating and see what modern chiropractic treatment entailed. I headed to a local chiropractor to find out. I had a half hour consult, with the report to follow (which will be discussed in a later post). At the end of the consult he recommended that I attend a talk they give explaining chiropractic because they have found that "when people understand why they are coming to see us in the beginning, they tend to respond a lot faster and stay well for longer". They call it a "new patient talk" or a "health talk" and suggested that I attend before my report so it will be in context of the modality.

The story continues...

It was a dark and rainy evening, and I battled valiantly through the wind and drizzle to get to the chiropractor's talk. The lights of office block were a welcome sight following the dark of the streets, and I stood inside the lobby cleaning the rain off my glasses with my top before ascending the stairs to the practice. I arrived to a bright and busy waiting room, containing a mix of men and women, mostly in their middle age or older. I expected to be directed to a meeting room for the talk but it turned out it was taking place in reception. A small flipchart had been placed on the reception counter by the receptionist who partook in some minor small-talk before heading home for the evening. The chiropractor gave us some general housekeeping notes and then we were ready to begin.

"Who here values their health?" he asked us, as an ice-breaker. We all put up our hands. "And who here wants to live 'til they're 100?". Everyone was much more equivocal as we all acknowledged that quality of life is just as, if not more, important than quantity. He went on to explain that children born today have a one-in-four chance of living until they're 100, and we're all living longer so we have to take care of ourselves as much as possible. So far, so uncontroversial.

"No Pain, No Problem"

Unfortunately, things went downhill pretty quickly. He said that society has this "myth" that if there's no pain, there's no problem, and if there is pain there is a problem, and used cancer as an example. He explained that pain can often be the last symptom you get with cancer, the last part of the "journey", the "straw that breaks the camel's back". Now, there are lots of examples of health problems where pain is not an initial symptom, but going to cancer feels a deliberate choice. It is something that almost everyone has knowledge of, either personally or through loved ones (in the audience of maybe nine of us, two women said they had been treated for cancer) and is something many people are legitimately scared about. To invoke cancer within the first five minutes of a "health talk", especially in the context of saying that you might have cancer without knowing it, is a great way of making people anxious about their health.

To emphasise his point that we can't take lack of pain as an indication our bodies are healthy, he used an example, this time in the form of an anecdote: a patient bent down to pick up something from the floor and his back went. The patient apparently thought that as the pain only started when he bent down, the problem only started then, but in fact he was a builder so the problem had been building until he reached a crisis point. Putting to one side the fact that it seems highly unlikely that this builder had had no pain at all until this fateful day when he bent over, the use of patient stories was concerning me. He had provided patient stories in my initial consultation and here were were again hearing about other patients. Had these patients consented to being used as sales pitches? Did they know that their chiropractor was sharing their stories with prospective patients? They may be anonymised but I have never had a doctor or a counsellor share details - however vague - of other patients during our appointments. It is a breach of trust and one that sat ill with me.

A Subtle Knife into the NHS

"Why don't we know about this on the NHS?" he then asked. "Why haven't we been taught this before?". Thus began a very strange part of the talk. He explained that the NHS is there to help us in a crisis - you wouldn't see a chiropractor for a heart attack - but that we need to take personal responsibility for our health. He said that heart disease and diabetes are two of the biggest costs to the NHS and they can both be eliminated if we take responsibility for our health.

He seemed to be implying that the NHS was not aware that pain was not the only symptom worth noting, that it did not recognise the importance of preventative medicine, did not deal in preventative medicine and that we had to take an individualistic approach to preventative healthcare. It's hard to know how best to unpick all this but I'll give it a go.

The idea that pain is the only symptom the NHS cares about is very odd, and completely wrong. The NHS has a fantastic online directory of conditions, giving readers information on symptoms, causes, diagnosis and treatment. Unsurprisingly, the Symptoms section is more than just "pain". Take abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), the first condition listed. It notes that,

AAAs do not usually cause any obvious symptoms, and are often only picked up during screening or tests carried out for another reason.

It goes on to say that some patients experience a pulsing sensation in their belly and may experience abdominal or back pain. Pain is just one of the symptoms. AAAs are deadly (my uncle died of one), often have minimal symptoms before they burst and have a very poor outcome if they do - the same webpage notes that "only about 2 in 10 people who have a burst aneurysm survive". Opening other conditions at random shows a similar recognition of symptoms other than pain and anyone who has been to the doctor will know they have to give more information than "it hurts!!".

The NHS may be what we turn to in a medical crisis, but it's not just for emergencies. The NHS has a big focus on preventative healthcare, and in getting people to take good care of themselves. They have campaigns to help people live healthier lives, including their Live Well campaign. This has information on diet, exercise (including their excellent Couch to 5K program which got me running, something I never thought possible), mental health, and a whole host of other topics. There is also the NHS Health Check which is "one of the largest prevention programmes in the world" and is estimated to have helped 7 million people since it began in 2013. The NHS runs many screening programs, testing asymptomatic people for potentially harmful conditions. The NHS works hard to help prevent people from getting sick and to suggest otherwise seems disingenuous (there's that word again).

While personal responsibility is, of course, an important part of healthcare and being an adult human, blaming people entirely for their poor health ignores the many genetic and societal causes. Type 2 diabetes and heart disease both have genetic components making it more likely some people will be affected than others. Food deserts - areas where it is difficult to buy affordable fresh food forcing people to rely on fast food for the majority of their meals - are thought to affect more than a million people in the UK. The links between poverty and poor health outcomes are well known and lead to a 19 year difference in life expectancy between the least and most deprived areas of the country. Now, it could be argued that if you're able to afford to visit a chiropractor you are able to afford to eat healthily, but perpetuating the attitude that personal responsibility (or lack of it) is the only reason for negative health outcomes further stigmatises those who already face struggles for having poor health.

The final statement, that heart disease and diabetes are two of the NHS's biggest costs, is from everything I can see, wrong. It's a nitpick, to be sure, and the most up-to-date figures I can find are quite old (2010/11), but mental health care is the largest expenditure, accounting for 11.1% of the programme budget. Neither heart disease nor diabetes were explicitly listed, but "problems of circulation" (which may include heart disease) and "cancers and tumours" were second and third in expenditure. You may ask why I bothered to look at this when it wasn't integral to his point. The answer is that I think that when you're positioning yourself as an expert and someone people should trust with their health you have a duty to be truthful and accurate with your information and from all the data I've been able to find he was not doing this.

The Most Important System in Our Body

We're not even 10 minutes in to this talk and I've already bored you all stiff. Sorry! Talking of stiff, we finally get to the backbone of the talk - and the backbone itself. We get shown a model of the spine and are informed that it has two functions: to create movement and to protect "the most important system in our body", the nervous system. The chiropractor explains that there are branches off the spinal cord which are nerves that go to the rest of the body and "control everything inside the body", they're like "the electrical cables of a house" and "without the information going down these nerves nothing will ever happen". In fact the nervous system "controls our organs.. [and] our immune system". We get a very crude drawing on the flipboard of a stick person to show that the information goes from our brain to our body and then goes back up to our brain, and are informed that only 10% of our nerves are able to signal pain, the other 90% "is basically just going on in the background". He tells us that this is important from a chiropractic point of view as this is were all the pain comes from and "how your body heals and how your body looks after itself all comes down through this nervous system" so if there's "interference" in this system that's where problems come from. Chiropractors are looking for those interferences in the spine and may refer to these interferences as "blockages" or "restrictions" or "subluxations". He shows how these manifest by taking his model spine and twisting a few vertebrae out of alignment. His job is to make sure the blockages are not in that part of the body so the brain can send its signals through properly. He used an analogy of a hosepipe with a kink in it, preventing the water from flowing. In the same way the a blockage in the spine prevents the nerve signals from flowing.

Okay. So. Where to start? Let's take the basic stuff first. The first is a nitpick, but an important one: the spine has three main functions, not two. The third function is that of support. It was, admittedly, alluded to, as he said that without the backbone we would be like a a jellyfish, but it's still surprising that such an important function is not named specifically.

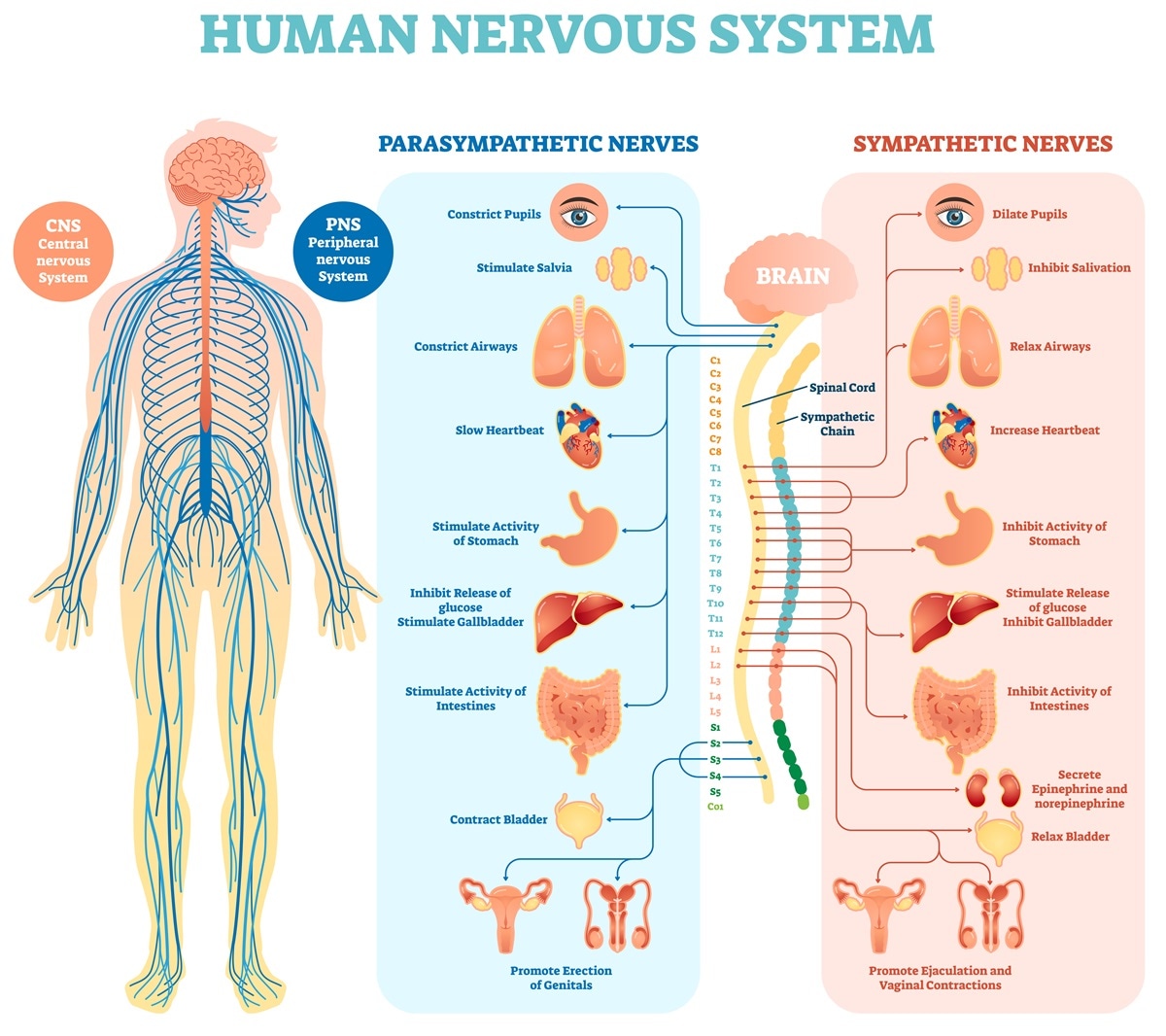

The explanation of the nervous system was incredibly poor. Now, I appreciate that this is a short talk to a lay audience about a complex subject but it really gave no real explanation of how the nervous system actually works. The nervous system is complicated but I'll do my best to give a basic overview, aided massively by this video and Wikipedia. The nervous system is divided into two parts: the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system. The central nervous system comprises the brain and the spinal cord. The peripheral nervous system is what is found in the rest of the body, and comprises nerves and ganglia. The peripheral nervous system is divided into three systems: the somatic, autonomic and enteric nervous systems. The somatic nervous system is the part that controls movement. When we refer to a "reflex action" like your knee jerking when hit with the doctor's hammer, we're referring to the somatic nervous system. The automatic nervous system regulates bodily functions, such as heart rate, breathing, and reflexes like coughing and vomiting. The "fight or flight responses" is largely controlled by this system. The enteric nervous system controls the gastrointestinal tract.

|

| Nervous system diagram [Source] |

You may have noticed I've not mentioned pain in that summary and that's because pain is only a small part of what the nervous system does. This is probably the source of the 10% statistic above, though the way it sounded to me was that he was saying that the other 90% were producing pain signals, we just weren't noticing them. In fact it's only one subset of sensory neurons, called nociceptors, that produce pain signals. The other sensory neurons are giving us things like sight, smell, and temperature. The other neurons, called motor neurons, are the ones that control things like movement and hormone secretion (these are the neurons affected by motor neuron diseases like ALS).

So, while there's nothing explicitly wrong with what he said, from what I can tell at least, the way it was explained was confusing and the implication of it all seemed to be that the nervous system is this mysterious and magical system and if we look after it then the rest of our body will remain healthy.

Subluxations

I want to spend a little bit of time talking about subluxations. It is a medical term, meaning a partial or incomplete dislocation of a joint or organ. Once the joint has been relocated back into the joint, further treatment may not be needed but if the surrounding tissue has been damaged surgery may be required to repair it. To prevent further subluxations of the joint physiotherapy may be recommended to strengthen the muscles surrounding it to ensure they hold it in place. This video, while wonderfully American and cheesy, gives a quick rundown of the manifestation and treatment of shoulder subluxations.

A partial dislocation of the back sounds like a pretty major thing, but remember that's not the alternative name the chiropractor gave. Instead he referred to subluxations as being "blockages" or "restrictions". Why not explain them as an incomplete dislocation? People would understand what's meant by that, surely, and far more than trying to understand what it meant by a "blockage". Well, it's because a chiropractic subluxation isn't an incomplete dislocation. A chiropractic subluxation is, well, a fuzzy concept. It is, to quote one chiropractor,

...an abstraction, an intellectual construct used by chiropractors, chiropractic researchers, educators and others to explain the success of the chiropractic adjustment.

The General Chiropractic Council, the body that oversees British chiropractors, states that,

While the World Health Organisation defines a subluxation as, The chiropractic vertebral subluxation complex is an historical concept but it remains a theoretical model. It is not supported by any clinical research evidence that would allow claims to be made that it is the cause of disease. [my emphasis]

A lesion or dysfunction in a joint or motion segment in which alignment, movement integrity and/or physiological function are altered, although contact between joint surfaces remains intact. It is essentially a functional entity, which may influence biomechanical and neural integrity. [my emphasis]

How does all this tally with the demonstration we were given where the chiropractor took his model spine and twisted several of the vertebrae out of alignment? Well, honestly I don't know. It's the sort of thing that you instinctively think is going to be extremely painful and highly noticeable but it seems the body is weird. This piece has a bunch of examples of people with extreme dislocations and spinal abnormalities who had no physical problems at all. In one case someone was born with part of a neck vertebrae entirely missing with no ill effects! If actual dislocations don't result in physical problems, how does a subluxation, where "contact between joint surfaces remains intact" cause so many? And if it remains intact what exactly is the chiropractor feeling for? Again, I honestly don't know. And the talk didn't explain.

This post has been far longer than I intended, and we're only half way through the talk. It reminds me of the infamous Gish Gallop - it is quick and easy to talk nonsense, but far slower and harder to refute it. Still to come are toxins, toddlers and much more. Tune in next time for our continuing Adventures in Chiropractic!

Comments