Edward Colston - One Year On

"There were protests around the world after the filmed murder of George Floyd, whilst being arrested in America. All Black Lives Bristol organised a protest against police brutality and racial inequality. On 7 June 2020, an estimated 10,000 people gathered in Bristol.

Protestors pulled down a statue of Edward Colston, graffitied it and threw it into the harbour. Four days later, Bristol City Council retrieved it. Museum conservators stabilised the condition and preserved the graffiti...

This temporary display is the start of a conversation, not a complete exhibition. we want to hear your views to help decide what happens to the statue next. Let's sketch out a plan for Bristol's future. All voices will be heard."

These are the words that greet visitors to the new consultative display on the statue of Edward Colston (1636 – 1721). It is a small display, tucked away in the corner of one of the galleries upstairs at M Shed. It is signposted by floor markings, and the numbers are controlled by a couple of attendants, one of whom asks every visitor to read the introduction before entering.

The Display

After the introduction we go around a corner and are given a bit more context,

There has been public debate about Colston's legacy and Bristol's involvement in the Transatlantic Traffic in Enslaved Africans for decades. The 2020 protest achieved what many anti Colston campaigns had not. The statue was removed and became worldwide news. It became part of a fierce debate about racial and class inequality, the past, and who is remembered in public space.

We are then told about the placards that were placed around the plinth and a very small selection are displayed.

The final entry on this wall shows the results of an online survey held by the local paper, Bristol Live, which was published on 12 June 2020 after receiving 10,252 responses in under 3 days. This non-random sample found that 56% of people thought "The protestors were right to pull [the statue] down and drop it in the harbour" while only 20% thought "It should not have been taken down by any means".

We then turn a corner. On the outer wall is a projection of images from the protest, the aftermath, and other news stories and landmarks concerning Colston's legacy in Bristol.

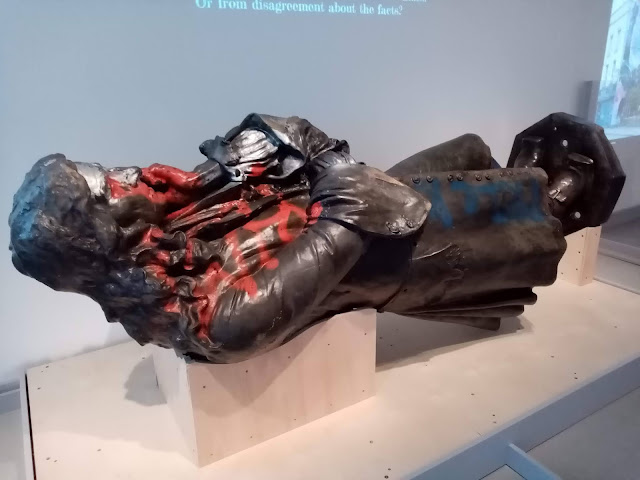

Beside this is the statue itself. It is laid down. There's a short barrier around it to keep people from getting too close but it is not obtrusive. The statue is on an octagonal base. It is of a man in breeches and a frock coat, one leg is slightly bent and he is holding his left hand to his chin while the right is used to support the right at the elbow. His shoes are rather strange, having the toes cut off so they end very abruptly, and remind me of the witches feet in the eponymous Roald Dahl book. He is wearing what I assume, given the time period, to be a wig of long flowing locks that rest on his shoulders. The legs and frock coat have been graffitied with blue spray paint. On the legs someone has written "BLM". The frock coat graffiti is illegible. The head and chest have been graffitied in red spray paint. There are words but the folds of the statue make them hard to make out. The eyes have been sprayed, as has the hand on his chin. There also appears to be some white on his forehead and on his left cuff.

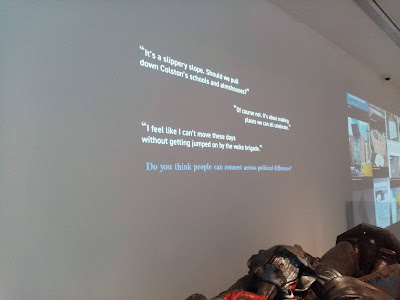

Above the statue the bare wall is used to project comments from unnamed people in response to various questions about statues and Colston. One question asks, "What is the purpose of statues and memorials?". The answers displayed include,

"Everybody knows slavery is wrong. But you can't change history."

"Statues don't teach history. They honour people."

"Colston's statue *has* taught me history. When I see it, I reflect on the bad things and feel grateful for the good."

At the end of this wall is a name-check to John Cassidy, the man who designed and sculpted the Colston statue, and a brief description of the aftermath of the protest on the statue,

"The breakages and graffiti are the result of actions taken during the protest. The stone plinth base remains in place in central Bristol. The pedestal (the top section of the plinth) is in storage whilst the future of the statue is decided."

On the other side is a temporary wall that asks "Who was Colston and why did he have a statue?". The text explains that Colston was,

"a high official of the London-based Royal African Company (1680-1692)"

and that this company,

"had the monopoly on the Transatlantic Traffic in Enslaved Africans until 1698. As such, Colston played an active role in the trading of over 84,000 enslaved African people (including 12,000 children) of whom over 19,000 died on their way across the Atlantic."

It goes on to explain that,

"When Colston died, he left about £71,000 to charity (comparable to over £16 million today). He had given money to schools, almshouses, hospitals and Anglican churches whilst alive too."

"In response to increasing class divisions the city's elite reinvented him as a patriarchal role model and an emblem of charity, 170 years after he died... The Colston statue attracted little financial support and was largely funded by a small number of anonymous donors."

And ends by touching on the way Colston's legacy was shaped over the years,

"Though Colston's role in the slave and sugar trade was widely known in some circles, popular histories and public narratives downplayed it. They highlighted his philanthropy instead."

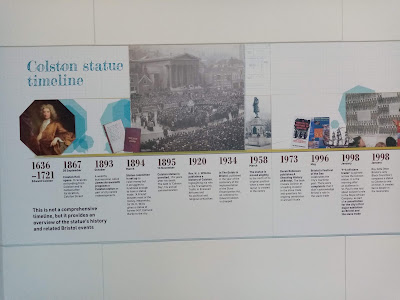

"This is not a comprehensive timeline, but it provides an overview of the statue's history and related Bristol events."

The timeline notes the back-and-forth that has existed for over 100 years between those trying to highlight Colston's (and Bristol's) links to the slave trade and those trying to hide them.

The opposite wall shows the results of a survey of 2,778 people asked if they agree with the statement "The Colston statue should be put on display in a museum in Bristol." 60% agree.Visitors are then asked to fill out the "short survey" which,

"will be used to inform [the We Are Bristol History Commission's] report to the Mayor to review recommendations on the long-term fate of the Colston statue."

My Thoughts

I've tried to keep my description of the display as objective as possible. It's what I saw, so there's going to be some subjectivity in there, but my intention was to walk you through the display and let you see what you want to see, not what I want you to see. I'm not entirely sure I've succeeded but I tried. And now's the time to add my thoughts.

So what do I think?

First, I want to start with the statue. That statue, so symbolic and meaningful that it seems the whole world has an opinion on it. Turns out it's pretty shit really. It's generic "posh white guy from olden times". There's no detail, the buttons on the frock coat are just circles with another slightly smaller circle in them. The wig is just a few locks and curls and the rest is just light impressions in the metal. And I really cannot get over the shoes. I didn't notice them when I was in the exhibition - I was focused too much on the head area to bother with the feet. But when I was writing the description I thought I'd better take a look and my goodness. It looks like the feet are too big for the base, so rather than make it bigger they've been cut to fit, like a victim of Procrustes.

The idea that this is a high-quality piece of art that needs protecting and preserving for its artistic merit seems pretty laughable to me. Honestly, the main thought I had when looking at it, lying prostrate and grafffitied, is that it is now far more interesting artistically than it has ever been. That pose, the necessary result of the damage incurred from its toppling, can be seen as reminiscent of the prone positions slaves were forced to keep while being transported across the Atlantic. Or even of the casual "arrogance, entitlement [and] disrespect" shown by people of Colston's class to the rest of us that continues to this day.

The graffiti, the physical manifestation of the disrespect the protestors felt towards the statue and the man it symbolises, takes this rather pedestrian statue and elevates it to a piece of significant art. I can't help but think of those spray-paint cans being wielded with fury and determination, and think of how many slaves were subjected to equally furious and determined lashings of the whip that left scars just as permanent.

|

| Wikipedia |

The brutalisation the statue was subjected to was far less, both in tenor and duration, than the brutalisation that so many men, woman and children received at the direction of Colston and men like him. But that it occurred at all is significant. It was a move that resonated around the world and led to a discussion about memorialisation and commemoration that was long overdue. That conversation hasn't, in my opinion, gone well, being misunderstood by those objecting to the removal of such monuments as an attempt to "rewrite" or "erase" history, which is the complete opposite of what is intended. But it's early days.

As for the display itself: I have to admit to being underwhelmed. On the one hand I can understand the desire to keep things simple and short - the less you say the less likely you are of receiving accusations of bias. But that silence is, in many respects, a form of bias itself. Silence can be complicity. And when the status quo has been, for so long, to not say anything and hope people will just leave things alone, to not say things now feels like a continuation of that approach.

The language in the display has been carefully chosen and I think it's worth examining. I'm not a linguist, but even to my untrained eye it was clear that language was being used to shape our views. The first thing that struck me, as soon as I read the introduction to the display, was how the focus was on proximate causes and ignored any broader context. Yes, the protests were sparked by the murder of George Floyd, but people get murdered all the time and rarely cause global protests. He was murdered in the USA, so why did people in Bristol protest begin to protest against police brutality and racial inequality? What was it that made a murder an ocean away resonate with people in Bristol so greatly that they took to the streets in vast numbers in the middle of a pandemic? Where is the actual context that explains why the protests took place? That they weren't simply an expression of solidarity but a recognition that the factors that led to his death are just as endemic here. But nowhere is that mentioned.

I was also struck by how the display was described as "the start of a conversation" when this is a conversation that people have been trying to have with Bristol authorities for decades. If it is a start of a conversation it's only because previous attempts have been so firmly rebuffed by those in positions of power.

The next panel states that "The 2020 protest achieved what many anti Colston campaigns had not." This feels like a dig, unconscious or otherwise, at those previous campaigns. Why were those campaigns unsuccessful? What could possibly have prevented them from being able to get this conversation started sooner? The problem, it seems in retrospect, was that those campaigns tried to operate within the law. They petitioned the Council to move the statue to a museum, or even to just put up a plaque that provided context next to the statue, but these petitions were dismissed. Those previous campaigns did not fail, they were failed. Failed by those in power. Yet nowhere is this context provided.

Then we have the information on the man himself. It says that he was "a high official of the London-based Royal African Company" but doesn't mention that he was deputy governor between 1689 and 1690. He wasn't just "a high official" but one of the highest.

The text is underlined in a couple of places, once under the number of people enslaved by the Royal African Company, and another under the amount Colston left to charity in his will. It's almost begging the reader to ask if the lives of 84,000 people is a price worth paying for the modern equivalent of £16 million to charity. What would balance the scales in your eyes? By the way, that's about £190 (modern day money) to charity for each person sold into slavery. Would you be willing to be sold into slavery if it meant your local school got £190 to spend on supplies? I certainly wouldn't. I'd like to think my life is worth more than that. Really, I'd like to think that there's no figure that's 'worth' the destruction of a life, particularly to a system as horrific as the trans-Atlantic slave trade, even if the resulting money does go to good causes. But by underlining and presenting these figures as two sides of an accounting book we are implicitly asked where our tipping point would be, and to presume that there is a tipping point that makes the sacrifice of someone's life to slavery worth the price.

The statement that "popular histories and public narratives downplayed [Colston's role in the slave trade]" is yet another case of the careful use of language. It feels like it's being balanced - after all, it's admitting that history has been shaped for specific aims. But it feels like it's trying to be the end of the story, rather than the start. The use of the passive voice is so important. "Popular histories [were] downplayed" but those popular histories didn't just emerge from the aether. They were written. By men. Men who had specific intentions. What were those intentions and why did they have them? We aren't told. I get the impression we aren't meant to ask such questions.

The more I look at the timeline the more interesting I find it, again for what it doesn't say more than what it does. Take one key date - 2018-9,

Debate over the wording of an additional temporary plaque to acknowledge Colston's involvement in the slave trade. Disputes aren't resolved so the plaque isn't added.

"Debate". "Disputes". Between whom? Who objected to a temporary plaque acknowledging Colston's involvement in the slave trade? Why did they object? It's a fact. He was an official in the Royal African Company for 12 years and was third-in-command beneath the Governor (the king) and the Sub Governor for a year. That's about as involved as you can get without getting on a slave ship or running a plantation. So why would anyone oppose having that information placed next to a statue of the man? This display certainly won't tell us.

The passive voice is used so much as to be almost comical. Take the event that precipitated this display, June 7 2020,

Colston statue is pulled down, rolled along the road and thrown into Bristol Harbour during an All Black Lives Bristol protest.

Who pulled the statue down? Passers-by? Police? Council members? Protestors? This doesn't tell us. It merely tells us when it happened, not who made it happen. This inability to give anyone agency or responsibility is endemic in the display and is very telling. It is ultimately an inability to ask people to take responsibility, either individually or collectively, for the things that have happened in this city.

In the back corner of one of the galleries in M Shed is a circular room. There is a wide doorway, but it's clear that this is separate to the rest of the gallery.

This is the exhibit that examines the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

I found the design intriguing. It was separate to the rest of the exhibition. There were mentions of the slave trade elsewhere but nothing major. Why was it separate? Why is it treated differently? Why is it tucked away at the back? It's like they don't want us to see it. Like they want it to be seen as not really about Bristol, as detached and not something that has links to the rest of the city's history. Maybe the idea is to get the visitor to think these things and confront those thoughts but the cynical part of me thinks that it's actually because they knew they'd have to do something on the topic but also knew that anything they did would get people angry at 'making everything about slavery' so compromised by shoving it in the back and hoping those people wouldn't notice, even if it meant that no-one else did either.

This room epitomised this whole thing to me. We all know that Bristol's wealth is largely founded on slavery. But no-one really wants to admit it. We'll talk about it a bit, if we have to, and if we can pretend that it wasn't really that big a deal, but really we'd just like to forget the whole affair and get back to admiring the floating harbour and the SS Great Britain and the Suspension Bridge and the Georgian buildings and not think about where the money came from to pay for it all. The Black Lives Matter protests last year threw that collective amnesia into disarray and no-one in authority has figured out how to deal with it. They say that "all voices will be heard" but this again feels like a sop to the status quo. They need to ask if maybe some voices have been heard for too long, and that maybe they should be made to shut up for once and let others speak.

![A still of the scrolling images relating to Colston's legacy in Bristol. The left-hand column shows a placard that reads "10 years for a statue, 5 years for rape", below is an image of an all lives matter protest standing in front of the Cenotaph with banners reading "Not Far Right". Last one is a photo of the sign for Colston Avenue and the beginning of a news story which is truncated. Second row has BLM graffiti which says "As a Black person in the UK" and then text which is too small to read. Below is a political cartoon showing various statues of men wrapped in chains connected together with Colston at the front and being toppled. Below is an image from an unspecified protest march. The final visible row has a placard reading "[protect] women not statues. Then a news article from Bristol Live titled "Countering Colston Call on Bristol's Society of Merchant Venturers to be disbanded".](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEi6-TdZeZ_0t_nPP2twCpBVxzMKrCV_n1Q3bvDcpzuwpXC6hKepzWao19RHncSfnic1Ux32wx0p8RdTCoAs4J4uCufbDCoOvvn3h4I2t-GLjRRG7iIjZ_dxJUbtLt6gQ0G2qFDgAFcF2G4/w640-h480/Fig+3.jpg)

Comments